A few months ago, I had a conversation with @landofMordor in My Cube Thread. After learning some interesting information about the history of Evolutionary Biology in recent college classes, I realized that some of what I learned actually applies to Cube design in strange and unique ways. This post will be reposted in my Cube thread, but it was long enough to warrant a thread of it's own.

Part 1: "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution."

Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky once stated, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution." This is a generally true statement, as an understanding of evolutionary biology has helped us to uncover the relationships between organisms that drive global ecosystems.

Last semester, I took a class on Ichthyology, with an emphasis on the evolution of vertebrae, jaws, and bone. For those of you who don't know, all vertebrates, including things like birds and mammals, are technically fish, as we all evolved from Sarcopterygian fish. As a result, there was an entire lecture about how Ichthyology shaped early theories about evolution. Our modern understanding of evolution is largely influenced by Charles Darwin's seminal 1859 work On the Origin of Species. However, Darwin was not the first to conceptualize evolution, nor were his writings forged in a vacuum. To find the seeds of evolutionary biology, we would need to go back over 300 years. In the 16th century, French Naturalist Pierre Belon was the first person to note the homologous bone structures in the bodies of Humans and Birds.

This 1555 pamphlet shows the similarities between human and avian anatomy, with many of the same bones being found in Humans and in birds. Belon's observations served as the foundation for what would become the field of comparative anatomy: the study of homologous structures between organisms. There were several hundred years when people tried to make sense of the structural similarities between organisms. While many early works in this field focused on how comparative anatomy fit with biblical scripture, it would eventually be used to aid in the creation of early evolutionary biology.

Part 2: The Economy of Nature

Thomas Jefferson, amateur scientist and third President of the United States, once said: "Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; or her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken." Jefferson's perspective is indicative of a common trend in science before the 19th century. The world was thought to be static, with things not often changing except as an act of some higher power. While enlightenment thinkers had begun to pose alternatives for the idea of a creator god, people had not really begun questioning how the world changed over time.

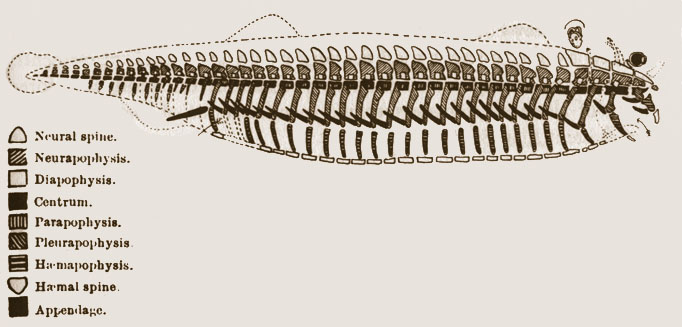

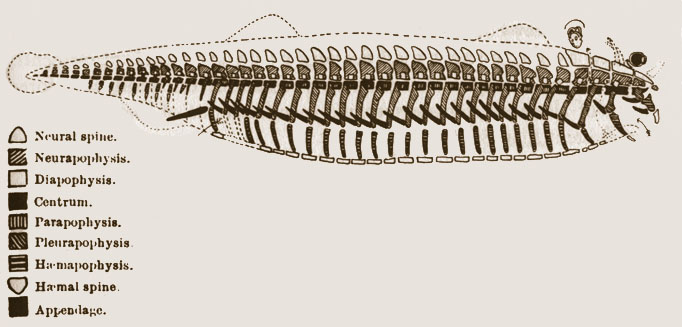

Everything changed in 1796 when Georges Cuvier published his paper On the species of living and fossil elephants. While some earlier thinkers called into question why, for example, fossils of marine creatures might be found on land, few assumed that these organisms were completely dead. Cuvier argued that some species of animal, specifically European Mammoths, had all died and become extinct. This revelation opened the doors to studying extinction: specifically how and why it happened. One thinker was Richard Owen. Owen was a biologist, comparative anatomist, and paleontologist. He described the first non-avian Dinosaurs, extinct Cambrian invertebrates, and many species of extinct mammals. By the 1840s, Owen came to the conclusion that an evolutionary process did occur. He proposed that all vertebrate organisms were developed from what he referred to as an Archetype.

According to Owen, an Archetype represented the common structural plan from which all vertebrates were derived in "ordained continuous becoming." Owen didn't believe a literal Archetype still existed somewhere in the world to be discovered. Instead, he believed the Archetype existed in a divine mind, which also "foreknew all its modifications." This model was capable of explaining extinction before the idea of natural selection was proposed by Darwin. Extinct species weren't truly gone: they represented a stage in the development of a species from the Archetype for all vertebrates into a new final Archetype for each individual class of vertebrate.

Owen's theory of Archetypes would later be dismissed once On the Origin of Species was published. Darwin's theory of natural selection, which was influenced by the works of cleric political scientist Thomas Robert Malthus and his writings on population growth and poverty, served as a more concrete explanation for the process of evolution. However, while Owen's thoughts on evolution may have no bearing on the field of Science, they could be useful in explaining trends in creative pursuits.

Part 3: Nothing in Cube makes sense in the light of Archetypes.

Natural selection is not a guided process. Evolution is driven simply by the needs of living organisms to survive in a specific ecological niche in a specific environment. There is no divine mind guiding the process toward a desired outcome. One example showing how natural selection can play out in nature can be seen in the 2003 paper What Darwin’s Finches Can Teach Us about the Evolutionary Origin and Regulation of Biodiversity. This study shows how the average beak size found in a population of finches increased after a drought destroyed most food on a remote island except for that which could be eaten exclusively by finches with a larger beak. As a result, Finches born in 1978 after the drought had an average beak size almost half a millimeter longer than cohorts born in 1976 before the drought.

View attachment 8002

Unlike natural selection, Cube design is an inherently guided process. Everyone has an idea of what they want their Cube to look like. While this idea can shift over time, many designers have some ideal Cube they are trying to build. Indeed, the early concept of "The Cube" as a monolithic format was essentially an attempt to find what could be called an "Owenian Archetype" for what a Cube should look like. This proved to be an impossible task for the early Cube community for a variety of reasons. For one, Cube design is a highly personal endeavor. Everyone has their own vision for their own Cube. As a result, one cannot force their ideas onto other designers who do not share the same vision for a Cube. Second, the "Archetype" is an abstract concept. While Owen was able to diagram what he thought the divine archetype for vertebrates might look like, his work is essentially speculation on what the archetype might look like. Archetypes for organisms do not exist in real life, so any "Archetype" someone invents in any context is going to be reflective of their own thoughts on a given subject and has no basis in objective reality. Third and finally, while Cube is not subject to true natural selection, it still faces some real selective pressures. Cubes can "go extinct" for reasons that don't always involve an active design choice. For example, a Cube's designer could quit playing Magic, leaving their ideal version of a given Cube unrealized. Design goals could shift, meaning that a Cube may no longer be built toward the same ideals as when it was started. Finally, new cards could be printed, which change what an ideal design might look like even with the same goals. Essentially, the singular Archetypal Cube can never come to fruition because the concept it represents fundamentally does not exist.

However, I would not be writing all of this just to come to the conclusion that the Archetype for a specific kind of Cube can't exist. While it is a fool's endeavor to try and fully encapsulate the entire Cube world in 360 cards, there are Cubes that essentially serve as the Archetype for most lists in a field. The best example is The Pauper Cube. The Pauper Cube is the brainchild of now-WOTC designer Adam Styborski. It was the first well-publicized rarity-restricted Cube in the Magic Community. After Styb's began employment at Wizards of the Coast, he handed development of the project to a board of prominent community members who are now responsible for updating and maintaining the Cube. While The Pauper Cube's goals have shifted over the years, it is essentially the Archetype for a whole branch of Cubes. Many designers in The Pauper Cube community refer to their Cubes as "mutations:" essentially evolutions of The Pauper Cube's Archetype to fit their own needs. Much like Owen's Vertebrate Archetype, each mutation of The Pauper Cube has split off from the mother list into a new unique variation.

Despite this, calling The Pauper Cube an Archetype for all Pauper Cubes is incredibly misleading. Looking at Lucky Paper's Cube Map, one can see that The Pauper Cube and its mutations make up only a small peninsula of a broader Pauper Cube island. While most of these Cubes share the same basic restriction (commons only), many are being built with entirely different purposes. Essentially, The Pauper Cube is an artificial Archetype. People use it as the Archetype for their own Cubes, but it's not representative of what all Pauper Cubes can or should be. Instead, The Pauper Cube serves as the Archetype for a community that all desire a similar type of gameplay. The main difference between The Pauper Cube and something like the old MTGSalvation Community's attempts at building an Archetypal Cube, therefore, is the fact that The Pauper Cube was designed by an individual (a "divine mind" in Owen's terms), and was later adopted by a community, rather than being created by a community and forced upon an individual.

Having said all of that, I do think The Pauper Cube plays an important role in the Cube community. One of The Pauper Cube's main purposes is to be an easy on-ramp for people wishing to start playing Cube. It's intuitive, inexpensive to build, and fun! Thanks to The Pauper Cube, someone wishing to start Cubing has an easy on-ramp to the format, with a dedicated community that builds variations of the same Archetypal Cube. Something like that just doesn't exist right now for unrestricted Cubes. The WOTC Cubes are expensive, and most Cube communities are fractured enough that there isn't really anything that serves as a good on-ramp to the format otherwise. The closest thing is The Penny Puncher Cube 2.0, which is both unlike both other Cubes and is no longer updated by its original creator. One might even say it's extinct, at least in its original form.

What I've realized through this process is that my original goal of building my new Highball 4K Cube was never to serve as a "platonic 360" Cube. Instead, I was trying to build something that could serve as a guide for building Cubes, trying to emulate the feeling-specific constructed formats. Sure, I wanted to offer a "definitive list" that could be copied by new designers (much like The Pauper Cube), but I always knew this idea was too narrow to encapsulate all possible 360 unrestricted Cubes. After all: Cube is not a monolith! Even after writing this now, I still hesitate to call my original goal the creation of an "Archetype" for anything other than my specific goal of "Cube that feels like the way TrainmasterGT remembers Theros-Khans era Constructed."

Part 4: See the Unwritten

Luckily, I don't think the effort I have put in so far to chronicle the creation of my Cube from a designer's perspective has been wasted. I think there is a real appetite for building Cubes with a retro gameplay feel without restricting the card pool. Andy Mangold recently discussed his new Neoclassical Cube in an episode of the Lucky Paper Radio podcast. The Neoclassical Cube aims to capture the feeling of late 90s/early 2000s Magic but is updated using new cards and mechanics that fit the spirit of old-school design. Andy is also making several aesthetic and Cube-management level decisions (such as using old, beat-up cards and playing the Cube unsleeved) to hit home that retro feel. Andy's goals a remarkably similar to my own goals, albeit with very different design directions thanks to our divergent eras and intended play styles. Given the positive reception to Andy's Cube, I definitely think there would be a desire to see a full recounting of my project when I eventually have the time to put pen to paper and nail down the list.

This exploration has revealed to me some key insights into my goals.

1: I want to show people how to build an updated Cube with older cards, not simply give them a list.

2: Any Cube I write about doesn't need to fit everyone's ideal of what a Cube should be.

3: If I want to make something for people to copy, I can do that, but I shouldn't design my main Cube with that goal in mind.

I was trying to build a Cube that could simultaneously act as a noncontroversial on-ramp for the format while still aligning with my own personal design sensibilities. These two goals are at odds with each other because what I want and what the public wants are not necessarily the same. However, I can and should still formalize my accounting of the design process for this Cube, as there is an appetite for this type of project. Now that I know that what I'm writing is more than just my own screaming into the wind, I have found a renewed purpose to finish my project. My secondary goals have definitely shifted, but my driving motivation of "catalog the construction of your ultimate Cube" remains strong. I still think I could build a singleton 360 version of my Cube for copying, but I would need testing resources beyond what I currently have to bring that to fruition alongside my main Cube. After all, that would be an entirely separate project with an entirely different primary goal.

Thank you for reading!

–GT

I had been resistant to the idea of removing the singleton restriction on the Cube since one of my initial goals was to write an article series about the design of this Cube, where the final result would be a "platonic ideal" 360 Cube. The fact is though, that I've been working on this project for over a year and I am still not to a place where I'm ready to write an article series. I think I'm close to a place where I can begin the series, but until then, I don't need to restrict my gameplay so people on the internet won't complain about design choices I made for articles I haven't even written.

Setting the bar high, wow! But I'm glad to read your realization that this goal may not be attainable -- at least, not at the same time that you're fulfilling your design goals and satisfying your own creative instinct.

If I just had to muse aloud about a "platonic ideal" cube, I'd say 1) the funny thing about platonic ideals is that Plato was wrong about nearly every mathematical/scientific theory he put forth, 2) probably most people would consider their own list as near-platonic for their own goals, or else they'd change their list, and 3) the only time people agreed about the platonic ideal cube was in the short interval between the invention of the Cube format and the creation of the second cube.

Part 1: "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution."

Dr. Theodosius Dobzhansky once stated, "Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution." This is a generally true statement, as an understanding of evolutionary biology has helped us to uncover the relationships between organisms that drive global ecosystems.

Last semester, I took a class on Ichthyology, with an emphasis on the evolution of vertebrae, jaws, and bone. For those of you who don't know, all vertebrates, including things like birds and mammals, are technically fish, as we all evolved from Sarcopterygian fish. As a result, there was an entire lecture about how Ichthyology shaped early theories about evolution. Our modern understanding of evolution is largely influenced by Charles Darwin's seminal 1859 work On the Origin of Species. However, Darwin was not the first to conceptualize evolution, nor were his writings forged in a vacuum. To find the seeds of evolutionary biology, we would need to go back over 300 years. In the 16th century, French Naturalist Pierre Belon was the first person to note the homologous bone structures in the bodies of Humans and Birds.

This 1555 pamphlet shows the similarities between human and avian anatomy, with many of the same bones being found in Humans and in birds. Belon's observations served as the foundation for what would become the field of comparative anatomy: the study of homologous structures between organisms. There were several hundred years when people tried to make sense of the structural similarities between organisms. While many early works in this field focused on how comparative anatomy fit with biblical scripture, it would eventually be used to aid in the creation of early evolutionary biology.

Part 2: The Economy of Nature

Thomas Jefferson, amateur scientist and third President of the United States, once said: "Such is the economy of nature, that no instance can be produced of her having permitted any one race of her animals to become extinct; or her having formed any link in her great work so weak as to be broken." Jefferson's perspective is indicative of a common trend in science before the 19th century. The world was thought to be static, with things not often changing except as an act of some higher power. While enlightenment thinkers had begun to pose alternatives for the idea of a creator god, people had not really begun questioning how the world changed over time.

Everything changed in 1796 when Georges Cuvier published his paper On the species of living and fossil elephants. While some earlier thinkers called into question why, for example, fossils of marine creatures might be found on land, few assumed that these organisms were completely dead. Cuvier argued that some species of animal, specifically European Mammoths, had all died and become extinct. This revelation opened the doors to studying extinction: specifically how and why it happened. One thinker was Richard Owen. Owen was a biologist, comparative anatomist, and paleontologist. He described the first non-avian Dinosaurs, extinct Cambrian invertebrates, and many species of extinct mammals. By the 1840s, Owen came to the conclusion that an evolutionary process did occur. He proposed that all vertebrate organisms were developed from what he referred to as an Archetype.

According to Owen, an Archetype represented the common structural plan from which all vertebrates were derived in "ordained continuous becoming." Owen didn't believe a literal Archetype still existed somewhere in the world to be discovered. Instead, he believed the Archetype existed in a divine mind, which also "foreknew all its modifications." This model was capable of explaining extinction before the idea of natural selection was proposed by Darwin. Extinct species weren't truly gone: they represented a stage in the development of a species from the Archetype for all vertebrates into a new final Archetype for each individual class of vertebrate.

Owen's theory of Archetypes would later be dismissed once On the Origin of Species was published. Darwin's theory of natural selection, which was influenced by the works of cleric political scientist Thomas Robert Malthus and his writings on population growth and poverty, served as a more concrete explanation for the process of evolution. However, while Owen's thoughts on evolution may have no bearing on the field of Science, they could be useful in explaining trends in creative pursuits.

Part 3: Nothing in Cube makes sense in the light of Archetypes.

Natural selection is not a guided process. Evolution is driven simply by the needs of living organisms to survive in a specific ecological niche in a specific environment. There is no divine mind guiding the process toward a desired outcome. One example showing how natural selection can play out in nature can be seen in the 2003 paper What Darwin’s Finches Can Teach Us about the Evolutionary Origin and Regulation of Biodiversity. This study shows how the average beak size found in a population of finches increased after a drought destroyed most food on a remote island except for that which could be eaten exclusively by finches with a larger beak. As a result, Finches born in 1978 after the drought had an average beak size almost half a millimeter longer than cohorts born in 1976 before the drought.

View attachment 8002

Unlike natural selection, Cube design is an inherently guided process. Everyone has an idea of what they want their Cube to look like. While this idea can shift over time, many designers have some ideal Cube they are trying to build. Indeed, the early concept of "The Cube" as a monolithic format was essentially an attempt to find what could be called an "Owenian Archetype" for what a Cube should look like. This proved to be an impossible task for the early Cube community for a variety of reasons. For one, Cube design is a highly personal endeavor. Everyone has their own vision for their own Cube. As a result, one cannot force their ideas onto other designers who do not share the same vision for a Cube. Second, the "Archetype" is an abstract concept. While Owen was able to diagram what he thought the divine archetype for vertebrates might look like, his work is essentially speculation on what the archetype might look like. Archetypes for organisms do not exist in real life, so any "Archetype" someone invents in any context is going to be reflective of their own thoughts on a given subject and has no basis in objective reality. Third and finally, while Cube is not subject to true natural selection, it still faces some real selective pressures. Cubes can "go extinct" for reasons that don't always involve an active design choice. For example, a Cube's designer could quit playing Magic, leaving their ideal version of a given Cube unrealized. Design goals could shift, meaning that a Cube may no longer be built toward the same ideals as when it was started. Finally, new cards could be printed, which change what an ideal design might look like even with the same goals. Essentially, the singular Archetypal Cube can never come to fruition because the concept it represents fundamentally does not exist.

However, I would not be writing all of this just to come to the conclusion that the Archetype for a specific kind of Cube can't exist. While it is a fool's endeavor to try and fully encapsulate the entire Cube world in 360 cards, there are Cubes that essentially serve as the Archetype for most lists in a field. The best example is The Pauper Cube. The Pauper Cube is the brainchild of now-WOTC designer Adam Styborski. It was the first well-publicized rarity-restricted Cube in the Magic Community. After Styb's began employment at Wizards of the Coast, he handed development of the project to a board of prominent community members who are now responsible for updating and maintaining the Cube. While The Pauper Cube's goals have shifted over the years, it is essentially the Archetype for a whole branch of Cubes. Many designers in The Pauper Cube community refer to their Cubes as "mutations:" essentially evolutions of The Pauper Cube's Archetype to fit their own needs. Much like Owen's Vertebrate Archetype, each mutation of The Pauper Cube has split off from the mother list into a new unique variation.

Despite this, calling The Pauper Cube an Archetype for all Pauper Cubes is incredibly misleading. Looking at Lucky Paper's Cube Map, one can see that The Pauper Cube and its mutations make up only a small peninsula of a broader Pauper Cube island. While most of these Cubes share the same basic restriction (commons only), many are being built with entirely different purposes. Essentially, The Pauper Cube is an artificial Archetype. People use it as the Archetype for their own Cubes, but it's not representative of what all Pauper Cubes can or should be. Instead, The Pauper Cube serves as the Archetype for a community that all desire a similar type of gameplay. The main difference between The Pauper Cube and something like the old MTGSalvation Community's attempts at building an Archetypal Cube, therefore, is the fact that The Pauper Cube was designed by an individual (a "divine mind" in Owen's terms), and was later adopted by a community, rather than being created by a community and forced upon an individual.

Having said all of that, I do think The Pauper Cube plays an important role in the Cube community. One of The Pauper Cube's main purposes is to be an easy on-ramp for people wishing to start playing Cube. It's intuitive, inexpensive to build, and fun! Thanks to The Pauper Cube, someone wishing to start Cubing has an easy on-ramp to the format, with a dedicated community that builds variations of the same Archetypal Cube. Something like that just doesn't exist right now for unrestricted Cubes. The WOTC Cubes are expensive, and most Cube communities are fractured enough that there isn't really anything that serves as a good on-ramp to the format otherwise. The closest thing is The Penny Puncher Cube 2.0, which is both unlike both other Cubes and is no longer updated by its original creator. One might even say it's extinct, at least in its original form.

What I've realized through this process is that my original goal of building my new Highball 4K Cube was never to serve as a "platonic 360" Cube. Instead, I was trying to build something that could serve as a guide for building Cubes, trying to emulate the feeling-specific constructed formats. Sure, I wanted to offer a "definitive list" that could be copied by new designers (much like The Pauper Cube), but I always knew this idea was too narrow to encapsulate all possible 360 unrestricted Cubes. After all: Cube is not a monolith! Even after writing this now, I still hesitate to call my original goal the creation of an "Archetype" for anything other than my specific goal of "Cube that feels like the way TrainmasterGT remembers Theros-Khans era Constructed."

Part 4: See the Unwritten

Luckily, I don't think the effort I have put in so far to chronicle the creation of my Cube from a designer's perspective has been wasted. I think there is a real appetite for building Cubes with a retro gameplay feel without restricting the card pool. Andy Mangold recently discussed his new Neoclassical Cube in an episode of the Lucky Paper Radio podcast. The Neoclassical Cube aims to capture the feeling of late 90s/early 2000s Magic but is updated using new cards and mechanics that fit the spirit of old-school design. Andy is also making several aesthetic and Cube-management level decisions (such as using old, beat-up cards and playing the Cube unsleeved) to hit home that retro feel. Andy's goals a remarkably similar to my own goals, albeit with very different design directions thanks to our divergent eras and intended play styles. Given the positive reception to Andy's Cube, I definitely think there would be a desire to see a full recounting of my project when I eventually have the time to put pen to paper and nail down the list.

This exploration has revealed to me some key insights into my goals.

1: I want to show people how to build an updated Cube with older cards, not simply give them a list.

2: Any Cube I write about doesn't need to fit everyone's ideal of what a Cube should be.

3: If I want to make something for people to copy, I can do that, but I shouldn't design my main Cube with that goal in mind.

I was trying to build a Cube that could simultaneously act as a noncontroversial on-ramp for the format while still aligning with my own personal design sensibilities. These two goals are at odds with each other because what I want and what the public wants are not necessarily the same. However, I can and should still formalize my accounting of the design process for this Cube, as there is an appetite for this type of project. Now that I know that what I'm writing is more than just my own screaming into the wind, I have found a renewed purpose to finish my project. My secondary goals have definitely shifted, but my driving motivation of "catalog the construction of your ultimate Cube" remains strong. I still think I could build a singleton 360 version of my Cube for copying, but I would need testing resources beyond what I currently have to bring that to fruition alongside my main Cube. After all, that would be an entirely separate project with an entirely different primary goal.

Thank you for reading!

–GT