By: Jason Waddell

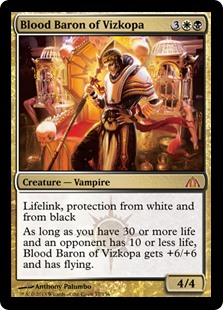

Earlier this week, forum member tomchaps posted about a new testing technique he read about on another forum. The idea is, when testing a new card, create your own “split card” between the proposed new card and the card that it would be conceivably replacing. The example given was an imaginary split card “Blood Baron of Vizkopa // Obzedat, Ghost Council”

The drafters would play with the split card, and could choose during games which side to use. After some testing, the following comment was made: “In the end, the numbers heavily favoured the Baron during the period where we had the Baron // Obzedat split card (and as a result, the Obzedat mode was never used).”

Through this exercise, the designer identified Blood Baron as the stronger card. As an academic exercise, we’re good so far. The question then becomes, what to do with this information. My central thesis in my writing has been to select cards that are good for your cube rather than good in your cube. This notion has been a bit contentiously received by some, but I think it’s helpful to take a step back and look at the abstract picture of what we’re doing as cube designers.

We are designing a game. Forget that this game is comprised of pre-existing materials from another game. Forget that Magic exists and just put yourself in the mindset of creating something entirely new. We can create whatever cards that we want, and have full control. It’s easy to create cards or moves that are powerful. Think of any game. Monopoly, Starcraft, Street Fighter, Dominion, triple Gatecrash draft. It’s trivial to think of moves, cards or mechanics that would be good in these games. Our job as designers is to decide what to make powerful. What kinds of decisions and gameplay to we want to incentivize.

“Development can make players do what we ask by putting the power of the set in the proper place.”- Mark Rosewater

Fortunately for this exercise, the example Blood Baron // Obzedat example has some issues. The first question is, do I want a card in this slot that is harder or easier to cast? One of the problems with a card like Armageddon is that its splashable mana cost meant that often it wouldn’t make its way to the white aggro player at all. I’ve often been heavily committed to a Rakdos deck, opened an Armageddon and easily splashed for it. With modern card design, Wizards is much more mindful of the color commitments required of cards, and often make a card harder to cast to bolster a particular archetype.

Next, we look at the card text. Blood Baron raises some immediate red flags. Many cubes are home to underpowered aggro sections, and another lifelinker would further compound this dynamic. Further, Protection effects have a tendency to randomly hose decks and produce low-quality games of Magic. Blood Baron is also extremely blunt. His value is driven by raw card power, and the design is not one that really gets me excited as a player. Obzedat also gains life, and has some possible protection from sorcery speed effects, with the added benefit of some decision making required once he is on the battlefield.

Either way, there’s a lot to consider beyond the raw power level of the cards. Perhaps neither card is appropriate.

Magic’s library is filled with cards that are good in cubes but not necessarily good for cubes. Cube writers and designers have complained for years about underpowered aggro archetypes, and I can’t help but feel that the problem is symptomatic of design philosophies that favor good cards over good environments.

Perhaps what is most overlooked in the whole discussion is that successful game design is often driven by specifically not giving players everything they want. You are your set’s design and development team. Where do you want the strength, and where do you want the weaknesses to be? What sort of trade-offs should your players have to make? How do you want to balance synergy versus raw card power?

Regarding the split card testing, I think it’s best suited for constructed testing, where you are really concerned with maximizing the power of your deck and clawing for every extra percentage point you can get. The split card testing method is engineered to force the player to answer the question “which card is more powerful” every time they encounter it. As a designer, you don’t even necessarily need to know the answer. Again, imagine you’re designing something like the upcoming Theros set. Your team of designers brings you 5 new card designs for a slot. It may be trivial to identify which is the most powerful card, but using that criteria is unlikely to lead to the most fun or cohesive set.

In my own design, I am debating between the inclusion of the following two cards.

Wretched Anurid has the higher raw power level, along with a relevant drawback, particularly when combined with recursive creatures (Gravecrawler, Bloodghast), or other life loss effects like Bitterblossom and Dark Confidant. It’s been in my cube for a while, and is a known quantity.

Blood Scrivener is the new kid on the block, and it’s hard to know how often its trigger is relevant, or whether it’s fun to build a deck that encourage playing empty handed, particularly when Blood Scrivener would be the only card in my cube that rewards emptihandedness.

At this point, I really don’t need more information on Wretched Anurid. The gains of running a “Blood Scrivener // Wretched Anurid” split card are twofold.

- It is easier to remember which cards are vying for the same slot.

- Players are more likely to include “Blood Scrivener // Wretched Anurid” in their decks than Blood Scrivener.

Both of these are artifacts of the fact that cube design is only pseudo game-design. Often we test only in competitive settings, with players who are less interested in testing than they are in winning. If you were working with a full-time team of designers, the other designers would be equally invested in testing and generating feedback for Blood Scrivener, rendering the split card method unnecessary.

As designers, we often make our best breakthroughs when we disregard what the player wants and give them instead tools they’ll enjoy. To borrow from another genre, one of Halo’s biggest innovations was that it restricted players to carrying only two weapons at a time. Prior to Halo, the shooter genre’s norm was to allow the player to carry every weapon in the game simultaneously. If given the choice, players will choose the more powerful “unlimited weapons” option. Choosing which two weapons to carry, however, turned out to be a very fun mechanic. Which of your existing weapons do you drop? What are the strengths and weaknesses of each weapon pairing? How much ammo does each weapon have left? What types of encounters do you expect to face soon?

Ultimately our job as designers is to make sure the strength of our set lies in the proper places. Players will power maximize, and our task as designers is to make the players’ power maximization process as fun as possible.

Discuss this article in our forums.